The 1981 Irish Hunger Strike started in the H Blocks of the Maze prison (also known as Long Kesh) in March and finished seven months later following the deaths of 10 Irish Republican prisoners. The mass support for the hunger strikers was to prove a turning point in Irish politics, but it resonated across the world.

I grew up 300 miles away in Luton, an English town albeit one with a large Irish community. The events had a profound impact on me as a teenager just getting involved in radical politics, it was heartbreaking following the news day by day of prisoners getting sick and dying in the face of the chilling, cold-hearted indifference of Margaret Thatcher and her Government. All the more so in that the five demands of the prisoners were quietly conceded shortly afterwards:

- The right not to wear a prison uniform;

- the right not to do prison work;

- the right of free association with other prisoners;

- the right to organize their own educational and recreational facilities;

- the right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week.

Luton had a significant role in the Irish republican movement in the 1970s and early 1980s, and was the scene of one of the last Hunger Strike demonstrations.

Frank Stagg and The Luton Three

An earlier hunger strike had been mounted by Irish prisoners in English jails in 1976, demanding a transfer to prison in Ireland. In the course of this protest Frank Stagg died in Wakefield Prison and Michael Gaughan died in Parkhurst. Frank Stagg had first joined Sinn Fein in Luton in 1972.

In November 1973, three members of Luton Sinn Fein - Sean Campbell, Phil Sheridan and Gerry Mealey - known as the Luton Three, were convicted of ‘conspiring to rob persons unknown'. No robbery had taken place and it was claimed that 'They were the victims of a trap laid by police agent Kenneth Lennon at the instigation of Special Branch. At the trial Lennon’s name and his role in the affair was concealed by the prosecution denying the defence any opportunity of contesting the basis of the police case. All three were sentenced to ten years' (Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 12, September 1981). In another twist Lennon (who lived in Francis Street, Luton) then encouraged an 18 year old Luton man, Patrick O'Brien, to take part in a plot to help the Luton prisoners escape from Winson Green prison in Birmingham. This seems to have been another Special Branch sting. Lennon later confessed his role as an agent provocateur to the National Council for Civil Liberties, shortly before he was found shot dead in the Surrey countryside.

The Luton Three all had a tough time in prison. Mealey spent seven weeks on hunger strike in 1976 as part of the same protest in which Frank Stagg died. While in Albany jail on the Isle of Wight, Campbell was badly beaten up by prison officers during a prisoners protest in 1976, sustaining a broken leg, jaw and ribs. Shortly after his release in 1982 he was admitted to hospital after suffering a severe stroke, but he went on to become a Sinn Fein councillor in Cookstown, County Tyrone until his death in 2002.

|

| 'They were taken to Luton Police Station where they were again assaulted and beaten and interrogated'. Republican News, 25 August 1973. The Patrick McAdorey Sinn Fein Cumann in Luton was named after an IRA volunteer killed in a gun battle out with the British Army in Belfast in 1971 |

In another incident in 1976 John Higgins, an electrician and the National Organiser of Sinn Fein in England, was arrested in Luton and later jailed for four years after being convicted of soliciting arms as well as walkie-talkie radios (Belfast Telegraph 7/4/77). He was convicted on the dubious evidence of John Banks, an ex-paratrooper and mercenary recruiter with links to the British intelligence. Higgins had earlier been the focus for an entrapment attempt from Kenneth Lennon.

|

| 'MI5's own mercenary - ex-Para set up Irish Republicans' |

There was also the odd case in 1977 when Luton Sinn Fein member Michael Holden was approached by Luton Labour Councillor Finbar McDonnell and asked if he knew about an IRA plan to bomb the Vauxhall car factory in the town - a false story apparently originating with police/security services. As Holden commented at the time: 'I don’t think that the IRA would bomb the Luton factory. They have never bombed factories. And, anyway we have 16 or 17 members of Sinn Fein working at Vauxhalls’. I asked who would benefit if such a thing happened — only our enemies would benefit. I said if a bombing was carried out there it would completely destroy all Sinn Fein activity not only in Luton but in the whole area' (statement in Hands off Ireland, November 1977).

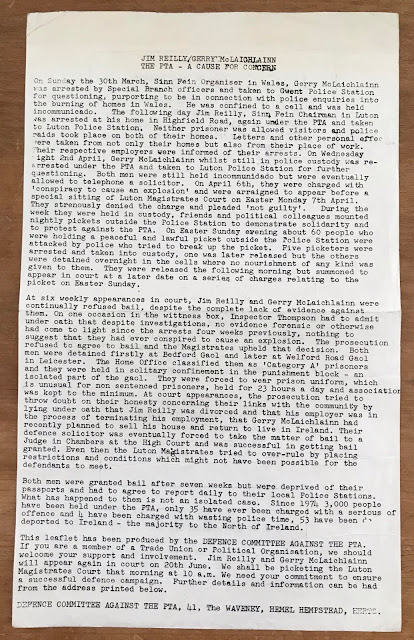

The Luton 2: Jim Reilly and Gerry MacLochlainn

The case of the 'Luton 3' was followed in 1980 by that of the 'Luton 2', which I remember personally. Jim Reilly was a familiar figure on the Luton Left, and had been a union shop steward at Vauxhall as well as the Home Counties organiser for Sinn Fein. He lived in Highfield Road in Luton's Bury Park area. As reported in Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! (no.4, May/June 1980):

'On Sunday and Monday 30 and 31 March two leading members of Provisional Sinn Féin (Britain) – Gerry MacLochlainn South Wales Organiser and Jim Reilly Home Counties Organiser – were arrested under the racist anti-Irish Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Sinn Fein and Hands off Ireland staged pickets of Luton police station, on one of which - on Easter Sunday - police piled in. 10-15 police rushed from the station and kicked and punched the demonstrators back from the entrance. This was followed by the arrest of five Hands Off Ireland supporters – four of whom were subsequently charged with ‘breach of the peace’.

That morning Jim and Gerry appeared in court and were charged with conspiracy to cause explosions. The conditions under which Jim and Gerry are being held also violate their rights as remand prisoners. Both men are forced to wear prison uniform and are being held on 23 hour lock-up in solitary confinement and denied association or recreation. Since being moved to Leicester prison, they have been held in the punishment block'.

Another Luton Vauxhall car worker, Willie Higgins, was also arrested under the PTA in April 1980, but was released without charge.

On 28 June 1980 there was a demonstration from People's Park in Luton calling for the dropping off charges against 'The Luton 2', as well as those arrested in the police station protest. Around 150 people took part in the demonstration which was addressed by Jim Reilly (by then out on bail) when it paused by Luton police station. The march had been arranged by Hands Off Ireland, the Revolutionary Communist Group's Irish campaign.

(The RCG did not have a branch in Luton, but there were a few members in nearby Hemel Hempstead including one of my teachers from Luton Sixth Form I believe. I recall them turning up at a Luton CND meeting around this time at the Communist Party HQ at 8 Crawley Green Road and trying unsuccessfully to get them to adopt a Troops Out of Ireland position. They spent a great deal of time denouncing other left factions for not having the 'correct' line on Ireland, but to give them their dues they did priortise solidarity when for much of the Left the fact that British troops were on the streets just across the sea was treated as background noise, just another issue on the menu of causes)

|

| Report of the Luton demo in June 1980, from FRFI, July/August 1980 |

I remember going to a public meeting at the International Centre in Old Bedford Road called by the Defence Committee Against the Prevention of Terrorism Act at which both Jim and Gerry spoke- the latter also having just been released on bail. I believe this was the meeting on June 19th 1980 mentioned in the following article, it also included a showing of a film 'Prisoner of War' about the prisoners' struggle.

|

| 'The racist anti-Irish Prevention of Terrorism Act... allows the police to arrest and hold people for eight days without any evidnce or charge, without any legal advice or contact with the outside world, and in atmosphere of intimidation and anti-Irish prejudice' |

The death of Jim Reilly

Sadly, Jim Reilly was to die shortly afterwards at the age of 54. A long time asthma sufferer, he was admitted to hospital with a chest complaint and died at St Mary's Hospital in Luton.

Born in the New Lodge area of Belfast in 1927, Jim Reilly was first interned in Crumlin Road prison as a young republican in 1942. After emigrating to England, he founded the Luton branch of Provisional Sinn Fein in 1971 and was arrested at least four times in the 1970s. For instance in 1975 Reilly and three other people from Luton including John Higgins were arrested in Liverpool as they left the Belfast boat on their way back from a Sinn Fein conference (Belfast Telegraph 31/10/75).

Reilly's treatment in prison was widely held to have contributed to his ill health, not to mention his earlier experiences of being on hunger strike as a teenage prisoner in the 1940s: 'Jim Reilly, Luton Sinn Fein and Home Counties Organiser, died in hospital on Friday 26 September 1980. Jim Reilly was a lifelong revolutionary Republican fighter working right up to the moment of his death. His death was a direct result of the frame-up organised against him and his close comrade Gerry MacLochlainn (now serving a six year sentence). Having hounded Jim Reilly throughout his life, British imperialism succeeded in hounding him to death in September 1980. Jim Reilly’s death was a great loss both to the Republican movement and the British working class. He will always be remembered as a courageous dedicated Republican and convinced socialist' (Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! No 12, September 1981).

As a final indignity, British Airways refused to fly his body back to Belfast, resulting in his funeral at St Peter's on the Falls Road being delayed. He was buried in Milltown Cemetery.

|

| Jim Reilly Obituary, from Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism, Nov/Dec 1980 |

Gerard MacLochlainn was jailed for 6 years, like me he ended up in Kent a couple of years later: he was in Maidstone Prison and I was at University of Kent at Canterbury! Gerry applied for a course at the University and was refused admission, I was involved in a short lived campaign in his support which involved painting 'Defend Gerry MacLaughlin' and 'Troops Out of Ireland' across the campus among other things (his name variously given in English and Irish spellings in different reports). I also came across him later on when he was the Wolfe Tone Society/Sinn Fein organiser in London in 1990s, I was in Troops Out Movement at the time. Later he moved to Derry and became a Sinn Fein councillor.

|

| Troops Out, December 1982 |

1981 Hunger Strike

Shortly after Reilly's death, in October 1980, prisoners in the H Blocks began a hunger strike in support of their five demands. This was called off after 53 days with the prisoners believing an agreement had been made. When it became clear that this was not the case, a second hunger strike began. Bobby Sands was the first to die on 5 May 1981, less than a month after being elected as MP for Fermanagh and Tyrone. Immediately afterwards the Government passed a law to stop prisoners standing in elections to ensure there would be no repeat of this.

Between then and the end of August, nine other prisoners died: Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O'Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine. All were volunteers with the Irish Republican Army or the Irish National Liberation Army. Kevin Lynch, who died on 1st August aged 25, had spent time in Luton including training with St. Dympna’s Gaelic Athletics Association club.

As the prisoners died they were replaced by others on the hunger strike and in September 1981 Sinn Fein announced that it planned a demonstration in Luton in support of the prisoners. In the event the demonstration was banned, along with all other demos in the town, after the neo-nazi British Movement announced its intention to stage a counter-demonstration. Not long before, on 11 July 1981, more than 100 people had been arrested in a full scale riot in Luton sparked by clashes between skinhead British Movement sympathisers and predominately Asian youth in the town centre. The threatened BM demo was the latest in a summer of threats from the group in the Luton area, and it provided a pretext for the Home Secretary to ban the hunger strike demo - not to mention the fact that Luton Town FC were at home to rivals Watford on the same day (for the historical record I will simply state that the mighty Hatters won 4-1).

However, a static Sinn Fein rally did go ahead in Luton's Manor Road recreation ground on Saturday 26 September 1981, which I attended along with about 250 people in the pouring rain. The speakers included prisoners' relatives including Nora McElwee (sister of Thomas McElwee), Malachy McCreesh (brother of Raymond) and Marius McMullen, brother of Jackie McMullen who was still on hunger strike (1). Other speakers included Michael Holden (Luton Sinn Fein),

Eddie Caughey (Sinn Fein prisoners support) (2) and ex-soldier Meurig Parri. Guest of honor was Owen Carron, who had been Bobby Sands' election agent and then after his death won the subsequent byelection on an 'Anti H-Block' ticket (3).

The British Movement had claimed that on the same day 200 - 300 people would protest outside Luton police station to protest against their march being banned (4)), but nothing materialised.

Just over a week later, on 3 October 1981, the hunger strike ended - but will never be forgotten.

|

| Troops Out, October 1981 |

At the time of the Luton riot in July 1981, the local Herald newspaper said: 'The scene could have been Belfast, or even Brixton or Liverpool' (16 July 1981). I think it's important to remember that the Hunger Strike was going at the same time as the 1981 uprisings in English town and cities. I have no doubt that the young people rioting in Brixton and Toxteth on the one hand, and Belfast and Derry on the other took inspiration from each other - the TV news was dominated throughout the year by such scenes. Many black and Irish activists definitely saw each other as both being in the front line against British imperialism - to take but one example, radical black magazine Race Today published a text by Bobby Sands. And of course the British state was also not slow in making such connections - in July 1981, the army demonstrated its water cannon to police chiefs and senior police officers from England visited their counterparts in the Royal Ulster Constabulary to learn about their methods of riot control.(1) Belfast Telegraph, 24 September 1981

(2) 'Troops Out demand by Sinn Fein’, Luton News 1 October 1981

(3) Special Category: The IRA in English Prisons, Vol. 2: 1978-1985 by Ruán O’Donnel

(4) Luton News, 24 September 1981.

Leaflets from my own colllection, The Splits and Fusions RCG archive was a useful resource

A couple more leaflets on the Jim Reilly/Gerry Gerard MacLochlainn campaign. This from the Defence Committee Against the Prevention of the Prevention of Terrorism Act:

|

| Back of leaflet advertising events in Luton |

'Luton Magistrate Obstructs Bail' - Hands Off Ireland press release:

[post updated March 2024 with information about John Higgins trial and Michael Holden statement]

More posts on Ireland